These seem rather disparate subjects, but somehow, they’ve become enmeshed in my mind. As to the first, I completed my novel two days ago. Well, the first draft anyway – it’s over five hundred pages so I know I have some trimming, editing, and underpainting to do. (I read about underpainting in a book writing guide by one of my favorite authors, and I thought it was a beautiful way to describe adding the essential details of sight or sound, touch or taste in a novel.)

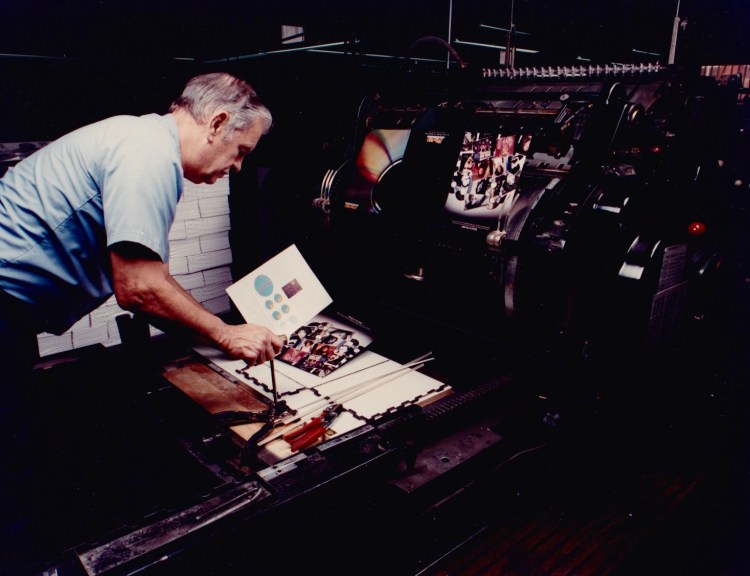

Perhaps the second half of my title isn’t quite so disconnected since most books (hopefully) are printed. The main character in my story is a young deaf man coming of age in the 40s and 50s and, it is loosely (very loosely) based on my dad – who was deaf and grew up in the same period. In my story, two of his deaf friends made a good living in the printing industry – as did my father and many of his friends in real life. The printing industry has long been a home for skilled deaf workers. It was thought they were at an advantage because the sounds of the big clanging printing presses wouldn’t bother them. In actuality, the vibrations that those machines made through the floor shook a body all day long. I’ve spent some time on a press room floor in my career as a print buyer and, it’s as tiring as the roar of the presses and you can’t wear ear plugs.

I was a print buyer for a magazine, software company, and the advertising industry for pretty much my entire career. It was accidental – kind of. I grew up around printing – my dad had an old Windmill letterpress in the basement of our home where he printed business cards and letterhead and tickets for raffles. That was at night and on the weekends to earn extra money. The man was a workhorse. Watching him with a small metal tray in one hand, standing in front of his big California cases of type, picking out the letters he wanted and placing them correctly in a form was fascinating since the letters are backwards. His fingers pulled those little backward letters as quickly as if they were going the right way. He’d set the form in the press, ink the rollers and then place a clean sheet in the feeder. It would roll onto the plate producing a readable image. Then he’d snatch the printed sheet out and efficiently, with no wasted motion or stopping the machine replace the printed sheet with a clean one. It was like watching a dance – graceful, not a step wasted. I went to sleep to the sound of that rhythm night after night and inhaled the smell of ink with my cookies and milk. And even though he couldn’t hear unless he put in his hearing aid – he’d sing along with his work –with no sense of the song’s original tune, somehow creating his own unique melody. It was years before I finally knew how Red River Valley was supposed to sound. One quick note about hearing aids – all they did for someone as deaf as my dad, who was profoundly deaf – was amplify sound. It didn’t allow him to distinguish one word from another. It did give him the gift of hearing music – not just from the radio, but the music of the wind in the trees or the roar of the ocean. When cochlear implants first became available, I asked him if he thought about getting one. He was in his late 60s, and he seemed to give it a lot of thought. Then he said, no, he didn’t think so. He liked being able to shut off all the sounds that his hearing aid gave him. He said he enjoyed the peace and quiet.

My story isn’t entirely my dad’s story, though I stole liberally from incidents and memories of his life. But it is his story – a story of a regular guy, making a living, having a family, buying a house – who just happened not to be able to hear.

These seem rather disparate subjects, but somehow, they’ve become enmeshed in my mind. As to the first, I completed my novel two days ago. Well, the first draft anyway – it’s over five hundred pages so I know I have some trimming, editing, and underpainting to do. (I read about underpainting in a book writing guide by one of my favorite authors, and I thought it was a beautiful way to describe adding the essential details of sight or sound, touch or taste in a novel.)

Perhaps the second half of my title isn’t quite so disconnected since most books (hopefully) are printed. The main character in my story is a young deaf man coming of age in the 40s and 50s and, it is loosely (very loosely) based on my dad – who was deaf and grew up in the same period. In my story, two of his deaf friends made a good living in the printing industry – as did my father and many of his friends in real life. The printing industry has long been a home for skilled deaf workers. It was thought they were at an advantage because the sounds of the big clanging printing presses wouldn’t bother them. In actuality, the vibrations that those machines made through the floor shook a body all day long. I’ve spent some time on a press room floor in my career as a print buyer and, it’s as tiring as the roar of the presses and you can’t wear ear plugs.

I was a print buyer for a magazine, software company, and the advertising industry for pretty much my entire career. It was accidental – kind of. I grew up around printing – my dad had an old Windmill letterpress in the basement of our home where he printed business cards and letterhead and tickets for raffles. That was at night and on the weekends to earn extra money. The man was a workhorse. Watching him with a small metal tray in one hand, standing in front of his big California cases of type, picking out the letters he wanted and placing them correctly in a form was fascinating since the letters are backwards. His fingers pulled those little backward letters as quickly as if they were going the right way. He’d set the form in the press, ink the rollers and then place a clean sheet in the feeder. It would roll onto the plate producing a readable image. Then he’d snatch the printed sheet out and efficiently, with no wasted motion or stopping the machine replace the printed sheet with a clean one. It was like watching a dance – graceful, not a step wasted. I went to sleep to the sound of that rhythm night after night and inhaled the smell of ink with my cookies and milk. And even though he couldn’t hear unless he put in his hearing aid – he’d sing along with his work –with no sense of the song’s original tune, somehow creating his own unique melody. It was years before I finally knew how Red River Valley was supposed to sound. One quick note about hearing aids – all they did for someone as deaf as my dad, who was profoundly deaf – was amplify sound. It didn’t allow him to distinguish one word from another. It did give him the gift of hearing music – not just from the radio, but the music of the wind in the trees or the roar of the ocean. When cochlear implants first became available, I asked him if he thought about getting one. He was in his late 60s, and he seemed to give it a lot of thought. Then he said, no, he didn’t think so. He liked being able to shut off all the sounds that his hearing aid gave him. He said he enjoyed the peace and quiet.

My story isn’t entirely my dad’s story, though I stole liberally from incidents and memories of his life. But it is his story – a story of a regular guy, making a living, having a family, buying a house – who just happened not to be able to hear.